The Templars are suing the Pope. Yes, over the inquisition. In a Spanish court.

[via Charlie Stross]

The Templars are suing the Pope. Yes, over the inquisition. In a Spanish court.

[via Charlie Stross]

Posters for the Watchmen movie that were used in Comic-Con have been uploaded to the movie’s site. Go look at them, they’re pretty.

What’s most striking about these is that most of them are meticulous recreations of the original Watchmen teaser ads that ran in the comics before the original comic series first ran. I’m not sure if those teasers appeared elsewhere since the 80s (presumably they might have been included in assorted complete editions as extras), but they’re certainly not iconic images to the casual comic reader. This is fan-service directed at the hardcore, which I guess is expected for Comic-Con, but it’s also consistent with every other bit of publicity I’ve seen so far. Zack Snyder and co. are making every effort to convince fans that this movie is going to be the unadulterated graphic novel put on film, as lavishly as 300 ever was. This message is clear even in their mass-market publicity.

To quote the X-Files slogan, I want to believe…

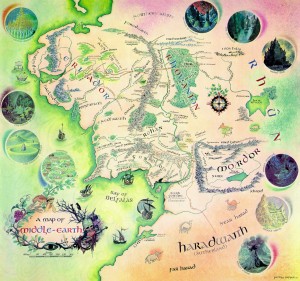

An appreciation of Pauline Baynes at Tor’s website, apropos the sad news she died recently. Pauline Baynes was the first artist to illustrate J.R.R. Tolkien’s books and C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series, and like Tolkien’s pals said, her art reduces the text to commentary on the drawings.

John Scalzi: The New Comprehensible, or, This is Not a Literary Manifesto, Thank God.

Now, let’s say that at this point, some writer out there is saying “Hey, I want to be part of this New Comprehensible movement in science fiction that I’ve heard so much about in the last four paragraphs,” and wanted advice on how he or she might go about doing it. What advice should this person be given? Well, manifestos are not my thing, but basic, practical advice? I can do that. Here’s what I would suggest, and it’s really rather simple:

1. Think of an actual person you know, of reasonable intelligence, who likes to read but does not read science fiction.

2. Write with that person in mind.

That’s all you do.

These were supposed to be thoughts on how I’d want to run an Amber game, but I didn’t get too far because of digressions into literary criticism.

First, we use just the first five books as our setting bible: Nine Princes in Amber, The Guns of Avalon, Sign of the Unicorn, The Hand of Oberon and The Courts of Chaos – only the Corwin books count. By removing Merlin’s story from happening and ditching everything revealed in those later five books we get rid of a whole bunch of inconsistencies and some horrendous cumulative power-creep.

Merlin’s version of reality sneaked into the Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game because the Logrus is mentioned in Courts of Chaos but demonstrated only in the Merlin books. So no Logrus tendrils in my game (or Benedict parrying invisible oponents either).

The tone and feel of the two series differs considerably. While the Merlin books are fantasy, as in genre fantasy shelved and marketed as such, and have (like Dave Langford astutely commented) the feel of a high-level AD&D campaign where the characters are weighed down by a slew of magic items, powers and artifacts, the Corwin books are Sword and Sorcery: published in the Seventies, this is first-generation fantasy, still fresh, still a shiny toy for Science Fiction writers (and readers); Phillip Jose Farmer and Michael Moorcock are clear influences, but Zelazney throws in Medieval Romance literature, Hardboiled detective fiction, Alice in Wonderland and Science Fiction’s love of big ideas and nifty extrapolations.

One notable difference between what I’m calling “Sword and Sorcery” here and second-generation fantasy, which is post-D&D, is the attitude to magic. In the first Amber series, magic is still mysterious and dangerous, subtle and sanity-shattering. You don’t have to be crazy to be a magician, but it helps (i.e, Dworkin and Brand). The magic we see worked by Corwin, Oberon and others looks like poetic improvisation, creative manipulation of shadow that resembled legend rather than the systematic spellcasting Merlin uses in the later books, which is very Vancian – that is, D&Dish.

About that power-creep: part of the appeal of the Amber books is that the scope keeps getting broader, with a series of revelations building up and the characters using their new insights to leverage established and newly-revealed powers in novel ways. That dynamic works beautifully in a roleplaying game. Even in the Corwin books, you wonder how the setting remained static for thousands of years if it could be upset so quickly, but in the Merlin books the power accumulates at an exponential* rate that’s just ridiculous. Ludicrous, even.

But back to the time period thing – Corwin’s books occur, according to this Amber Timeline some time around the period they were written – 1968-1977 or so. I want to keep my game close to that, so in my world it would be 1981 or so – no cellphones and WWW on shadow earth!

* – thanks, Ori.